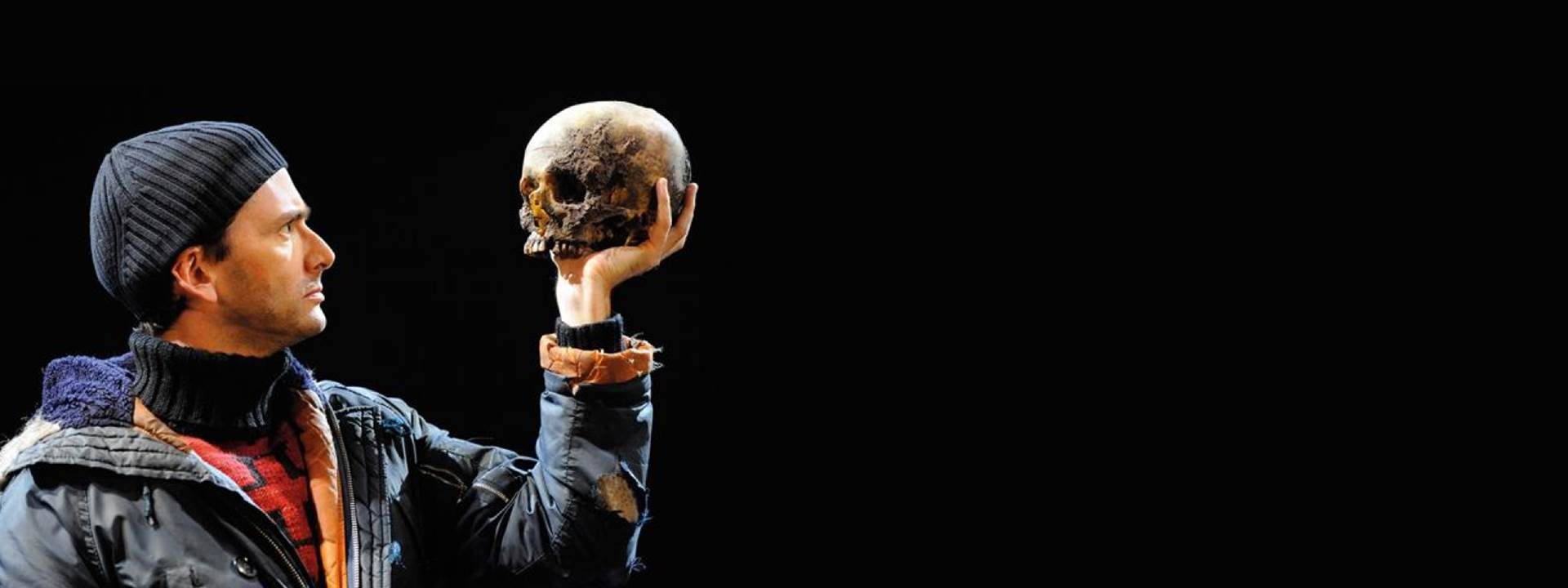

BANISH YOUR INNER HAMLET

news

In the Press

Published by

Charles Vallance

Date

25/06/2017

When I began my first planning job, I worked with an account man called Tom Rodwell. Tom taught me many useful things, including his three rules of eating abroad. “Never eat the local specialty” is the one I remember best and still observe to this day – the logic being, if the speciality was any good, it wouldn’t have remained local for very long (think faggots versus Yorkshire pudding or tripe versus Scotch egg). Local specialities are, as a rule, a provincial restaurant’s way of getting tourists to eat something they couldn’t otherwise sell – generally from the shadier end of the offal spectrum.

It was the late 1980s and, although things were infinitely slower than they are today, there was a detectable whiff of acceleration in the air. Tom neatly summed up the situation after a truncated lunch at Zazou, one of Charlotte Street’s more fashionable eateries: “When I was at BMP, you only had to do one thing a day. Now, you often have to do two things a day.” He paused ruefully before adding: “And, sometimes, even three things a day.”

I remember sharing his quiet sense of foreboding, tinged with lethargic dread. What was the world coming to? If we did three things a day, five days in a row, we would end up doing 15 things a week. This clearly was not sustainable. Either Zazou would have to shut or we would work our fingers to the bone. Zazou shut six months later.

So here we are in 2017, fingers duly ossified and, in my view, something strange has started to happen. There’s a danger of us reverting to old habits – of having less rather than more to show for our labours at the end of each working week. We may have passed the point of peak activity. In common with other sectors of British industry, we seem to work more but achieve less, with productivity stubbornly flatlining. The trouble is we no longer fill our unproductive hours with agreeable jaunts to Zazou, L’Etoile, The Little Acropolis, The Valiant Trooper or The Northumberland Arms. Instead, in keeping with the vogue of self-denial, we fritter the time away ostensibly working but, in fact, getting nowhere.

The process is insidious but by no means irreversible. Nor is it undetectable. The symptoms normally present themselves in the form of a sudden outbreak of meetings, all of which have long-winded but essentially meaningless titles. Beware, for instance, the Competence Assessment Transferability Clinic or the System Recalibration Accountability Plan. Run a mile from any KPI Platform Alignment Programmes and steer well clear of anything styling itself a Programmatic Transparency Onboarding Audit. Needless to say, these titles are fictitious – but only just. None of them is a million miles away from the kind of meeting that, if left unchecked, can cloud up a diary as quickly as algae can spread across a summer pond.

Why are these meetings proliferating? Why do we spend so much time talking about talks, often swaddled in opaque, impenetrable jargon? I put it down to our inner Hamlet. The vacillating prince is inside all of us, looking for an opt-out, a way to postpone a decision or duck out of the crosshairs of its consequences. And the reason our inner Hamlet is getting the upper hand is that the spirit of the age is with him. We live in naturally consensual, consultative times. A desire to include all stakeholders through a plethora of feedback mechanisms means that the cutting edge of decisiveness can quickly be blunted. Too often, instead of coming to a conclusion, the can is kicked down the road and another meeting is called. “And thus,” as Hamlet soliloquised, “the native hue of resolution is sicklied o’er.”

I find that one of the best ways to banish our inner Hamlet is to restrict the amount of time available for a task. Six weeks is nearly always better than six months. The tyranny of the deadline means that only those with the most at stake are involved and time is used much more rewardingly. The meetings are fewer, smaller and shorter, and revolve around the need to deliver a finished, concrete product – as opposed to a Marketing Matrix Feedback Stack.

Looking back to the 1980s, perhaps ten things a week wasn’t a bad return. To be honest, I’d settle for five rather than hear the sound of another 50 cans being kicked down the road by Hamlet and his merry crew of procrastinators.